Home

Henry James

Justice Holmes

About Me

Blog

Send me an e-mail

Links:

Wikipedia: Constitutional Monarchy

Eleanor I and

the Universal Charter of Human Rights

Lord Chief Justice O.W. Holmes

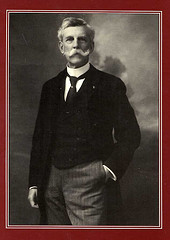

Henry James, Baron of the Cinque Ports

Right here at the beginning I

want

to put your mind at rest about the practicality of this proposal.

Since a constitutional monarch would be powerless, almost by

definition, the office needn't be part of the government at all.

No alteration

in the constitution nor any action by Congress would be needed. A

not-for-profit corporation (with a board of

Electors) could choose the monarch, perhaps from among the out-of-work

royalty of Europe who have been educated for such a task.

We might call our monarch the "Grand Panjandrum," since "king" and "emperor" have evil connotations. (Other suggestions?) The proper form of address would be one that George Washington jocularly suggested for the president of the United States, "Your High Mightiness."

Obviously, funds would have to raised to purchase an ancestral estate for the new royal family, perhaps somewhere in the southwest, to build and furnish a castle, and establish an endowment that would provide a suitable income for the panjandrum, who would be free to devote himself (or herself) to charitable works, lending his name to environmental and conservation groups, and other traditional activities of monarchs. (Something fairly modest, as monarchies go; nothing like the fabulous wealth of the Queen of England.) Contributions for this purpose to a non-profit educational corporation established for the purpose might even be tax-deductible.

The main point of all this would be for the Grand Panjandrum to embody the national identity of the United States of America, to represent us to the world, and to articulate our fundamental principles of equality, diversity and human rights. The Grand Panjandrum would embody the nation, and so keep this powerful role out of the hands of politicians.

The reason we don't have such a figure provided for in our constitutional system is that the drafters of the constitution could not agree as to whether the United States were a single nation or not. Most seemed to think of the confederation of former colonies as an empire, under a single government; but coud not agree that the scattered European settlements, interspered with American Indian nations and large involuntary settlements of Aftricans, were a single nation in the European sense. The chief executive was to be called a "president," which was understood to be a name for a weak official similar to the chairman of a committee. (The presiding officer of the Senate was also to be called a "president.") The electoral college and the Congress were both to be organized state by state, and each state had its own popularly elected governor, a more nearly monarchical post. Americans were citizens of their state; no national citizenship was defined. There was no need for a titular monarch for the enterprise as a whole.

But the Civil War settled the dispute; America was a single nation, defined by national citizenship for the first time. Over the course of two hundred years, successive presidents have gradually worked their ways around the original system of Congressional supremacy, often with collusion of the party in control of Congress. The result has been that president has or can claim near-monarchical powers. Candidates are chosen not for abilities or experience in government, but for their ability to play the role of ideal American, the embodiment of our wishful self-image. No wonder actors have been successful in politics.

Perhaps, if we had a Grand Panjandrum to attend state funerals and appear on television in time of war, to stand at the national altar and offer up the national prayers, we would be spared having politicians play the role of king, and seize the power of an actual monarch.

We might call our monarch the "Grand Panjandrum," since "king" and "emperor" have evil connotations. (Other suggestions?) The proper form of address would be one that George Washington jocularly suggested for the president of the United States, "Your High Mightiness."

Obviously, funds would have to raised to purchase an ancestral estate for the new royal family, perhaps somewhere in the southwest, to build and furnish a castle, and establish an endowment that would provide a suitable income for the panjandrum, who would be free to devote himself (or herself) to charitable works, lending his name to environmental and conservation groups, and other traditional activities of monarchs. (Something fairly modest, as monarchies go; nothing like the fabulous wealth of the Queen of England.) Contributions for this purpose to a non-profit educational corporation established for the purpose might even be tax-deductible.

The main point of all this would be for the Grand Panjandrum to embody the national identity of the United States of America, to represent us to the world, and to articulate our fundamental principles of equality, diversity and human rights. The Grand Panjandrum would embody the nation, and so keep this powerful role out of the hands of politicians.

The reason we don't have such a figure provided for in our constitutional system is that the drafters of the constitution could not agree as to whether the United States were a single nation or not. Most seemed to think of the confederation of former colonies as an empire, under a single government; but coud not agree that the scattered European settlements, interspered with American Indian nations and large involuntary settlements of Aftricans, were a single nation in the European sense. The chief executive was to be called a "president," which was understood to be a name for a weak official similar to the chairman of a committee. (The presiding officer of the Senate was also to be called a "president.") The electoral college and the Congress were both to be organized state by state, and each state had its own popularly elected governor, a more nearly monarchical post. Americans were citizens of their state; no national citizenship was defined. There was no need for a titular monarch for the enterprise as a whole.

But the Civil War settled the dispute; America was a single nation, defined by national citizenship for the first time. Over the course of two hundred years, successive presidents have gradually worked their ways around the original system of Congressional supremacy, often with collusion of the party in control of Congress. The result has been that president has or can claim near-monarchical powers. Candidates are chosen not for abilities or experience in government, but for their ability to play the role of ideal American, the embodiment of our wishful self-image. No wonder actors have been successful in politics.

Perhaps, if we had a Grand Panjandrum to attend state funerals and appear on television in time of war, to stand at the national altar and offer up the national prayers, we would be spared having politicians play the role of king, and seize the power of an actual monarch.